Introduction

![Mt Shasta - Hotlum Headwall]() The north side of Mt. Shasta

The north side of Mt. Shasta

This is written with the intention of sharing the insights gained from the Mt. Shasta tragedy in hopes that others can take away some valuable lessons, or offer further insight. Much of this has come from personal reflection, discussion with

MANY people, and additional research into the topics, both for my peace of mind and in an attempt to understand and learn.

I’ve attempted to find fault with myself in hopes of learning for the future, but after much reflection and research, I have yet to find any ‘mistakes’ we made that could have been foreseen as such, which is why I've chosen to continue climbing and am doing so with a clean conscience. It’s much easier to judge than to understand, it’s easier to spout vitriol than to sympathize, hindsight is 20/20, and I could care less about pandering to those who choose to take these easy attitudes at the expense of other people. So this article is not for them.

There are lessons to be learned, though, and I’m writing about them in the spirit of education and safety that Tom and I shared.

![Tom Bennett]() Tom practicing construction of a V-Thread anchor.

Tom practicing construction of a V-Thread anchor.Altitude Illness

There wasn’t much for me to learn here, as later research revealed that I did everything right and had a full awareness of what was happening and what to do. Still, many people have asked me about the ‘what ifs’ for Tom’s HACE and whether any actions could prevent such an outcome in the future. Sadly, my answer would be a resounding “no”, but I’ll address the points here.

For those that aren’t familiar with high altitude ailments such as High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) or High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE),

Altitude.org has a good summary.

HACE Prevention

HACE can occur at elevations as low as 6,500 ft, only 1% of people who ascend above 9,000 ft get HACE, and the vast majority of those cases occur above 16,000 ft. It is almost always preceded by symptoms of Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS). Tom never reported any symptoms and I never saw any expressed. By Tom’s reports and behavior, he showed signs of acclimatizing. If there were any signs, they developed overnight and were subtle enough that Tom couldn’t feel anything wrong until he stood up.

Over-hydration can be a cause of HACE, but although Tom hydrated a lot on Saturday, by Sunday morning he was more likely to be mildly dehydrated.

The probability of Tom developing HACE at 14,000 ft was extremely small, especially considering that the previous two days we slept at 5,000 ft & 10,000 ft, and had ascended to nearly 14,000 ft or higher twice. He had been getting up high regularly the past few months and never showed any susceptibility to altitude.

About all that can be learned here is that even those who don’t appear to suffer from altitude can still develop HACE, people that seem to perform well at altitude can still develop HACE at moderately high altitudes, and that one is never completely safe from this sickness when entering the mountains.

HACE Treatment

The only permanent treatment for HACE is immediate descent. That is why instead of calling 911 immediately, I attempted to get Tom down until it was evident that this was impossible to do. He was so far gone that even in good weather, without a sled it would have required a team of people to carry him down.

There are three treatments that can aid in descent while suffering from HACE that people have asked me about. One is administering oxygen directly, another is the hyperbaric or Gamow

(pronounced ‘gamov’) bag, which simulates lower altitude, and still another is administering an injection of dexamethasone.

First, for both of these I’d have to say that the winds blowing over Avalanche Gulch were so strong, and the rest of our descent options technical enough, that I doubt either of these could have improved Tom’s condition well enough for him to descend.

Gamow bags are large enough, expensive enough, and heavy enough that only expeditions to the high altitudes of the Andes and Himalayas can justify bringing them. Similarly for bottled oxygen, so carrying such things to the summit of Mt. Shasta is impractical and unrealistic considering how unlikely the need is compared to other first-aid needs.

Dexamethasone is the only thing that one could feasibly carry to Mt. Shasta’s summit, but it is not necessarily a viable solution. It requires a prescription and not everyone can get it. For example, I tried to get some for myself when I was procuring prescription drugs for altitude ailments from physicians for my climb to the summit of Denali (Mt. McKinley), the highest summit of North America where HACE and HAPE are common. Though I could get some prescription drugs, I was unable to get this drug from my doctor for 20,320’ Denali, so I suspect that many people could not get it for 14,162’ Mt. Shasta.

Mountain Search-and-Rescue Calls

During this ordeal, I saw a number of problems with communicating important details to Mountain Search-and-Rescue (MSAR) that resulted from both ends of the phone line. Making a call for a rescue and communicating vital information seems simple enough, but in reality there are a number of factors that make this very difficult to achieve, thereby delaying rescue and increasing confusion in rescue attempts.

I want to emphasize, though, that none of these improvements to my communication with 911 & SAR would have changed the outcome on Mt. Shasta.

When making a call for an MSAR, a few factors may make it difficult to properly get across the necessary information to those on the ground who are knowledgeable about the mountain and can make use of it:

- Low battery power.

- Bad reception (and an inability to know what the operator could actually make out from your garbled call).

- Short periods of reception.

- Transferring details from 911 to SAR to the field commander to the climbing rangers. It seemed to me that some details that were important were not delivered to the rangers because they were given trimmed down information from people higher up in command who didn’t know the mountain as well or what information was important.

In light of these problems and after talking with others about them, I’ve boiled down some possible solutions unique to calling in an MSAR that could be useful individually or in combination:

Personal Locator Beacons (PLB)

- Purpose: Communicating your exact position and requesting a rescue to that location.

- Pros: Unit is left off until needed. Message is sent out quickly, with no garbled transmission, and the location can be seen on a digital map such as Google Maps or entered into a GPS unit. Vital information for locating the rescue location is directly communicated to the rescuers without need for knowledge of the area. There is no need for cell phone reception as the units use satellite reception and are as such more reliable in getting a message out. The units are about as small and light as an avalanche beacon and are inexpensive, with the main cost being the annual subscription to the service provider.

- Cons: Cannot specify the needs of the rescue call or the urgency of the rescue. Cannot receive instructions from rescuers.

- Comments: In the case of Mt. Shasta, I had one on the mountain for sending position locations to family and friends for fun. I left it in the tent, but in the long run this oversight was inconsequential. The only way a PLB would have been helpful here was that if I didn’t make it off the mountain alive, rescuers could at least locate Tom’s body, and if I perished on the descent, they might have been able to locate my body if I sent out another distress signal from my final location. Still, in light of the difficulties in communicating our position to 911, I'll be more likely to carry one with me in the future.

|

| SPOT is a small, lightweight, and easy to use personal locator beacon. |

Texting

- Purpose: Getting information across intact when the phone is low on battery power or reception is a problem.

- Pros: Requires less battery power to write and send a message. You are more likely to get out a text message than to get a call connection, and you need less time to send the message so are less likely to get cut off. The information won’t come through garbled.

- Cons: 911 and MSAR probably isn’t set up to receive these sort of calls in many areas. With regular cell phones, texting a message takes a while so back-and-forth communication would be difficult in extreme environments.

- Comments: This could be an excellent way to get out a ‘first’ call, with location, names, rescue needs and urgency. I’ve found texting to be more reliable than phone calls in brief communications with climbing partners in the mountains.

Emergency Contact as an Agent

- Purpose: To have someone pre-briefed such that they can act in your behalf in making an MSAR call. You call them with the most pertinent information and let them call the local MSAR to provide most of the rest of the information.

- Pros: The person already knows your itinerary, ascent route, car location, name of party members, and possibly even the area based on a pre-trip briefing. All that you need to do when calling in a rescue through them is to tell them your location (which they should be able to make sense of easily since they are familiar with your route), and needs specific to the rescue. They can provide MSAR with your phone number if they want to attempt to talk with you directly, but this is less critical than if you’re the only one calling in.

- Cons: Hard to see any except there is a 3rd person involved in the communication.

Agent (Digital Style)

- Purpose: Same as the regular “agent” solution except your contact can provide MSAR directly with your itinerary in written and map form. If your emergency contact has digital copies of your route itinerary and map, they can deliver these directly to MSAR.

- Pros: MSAR has much better information about your whereabouts and kicks the pants off of any wilderness permit used for such rescues. Rescuers can have a map showing your exact intended routes and camps, in addition to any other trip information that you left with your emergency contact.

- Cons: There is no system set up for this to my knowledge, so you’d need to do some work ahead of time, such as finding out where to send the information, and how to make sure it is received.

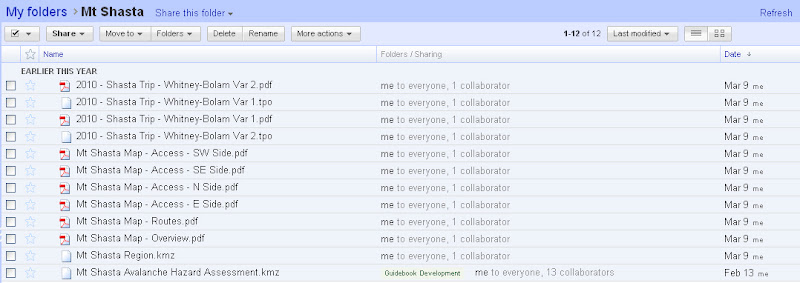

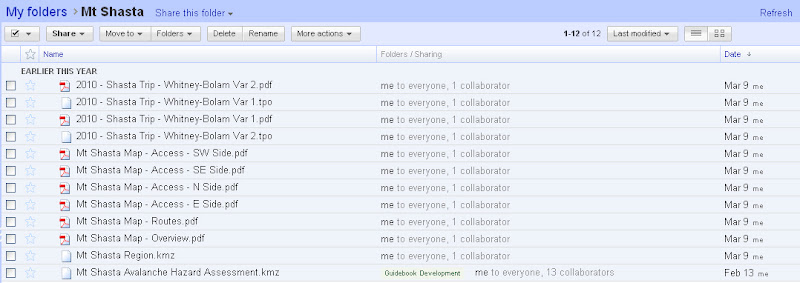

- Comments: I shared a typed itinerary and annotated map of our travel plans with friends via Google Docs, which was easily shared by e-mailing a link. Once my community of friends became aware of Tom's plight, someone thought to attempt to e-mail this to the local authorities. It never got anywhere, but it could have been useful to the rescuers if it had.

|

| A Google Docs folder, which can be used to easily share maps and itineraries amongst many people. |

Electronics and Cold Weather

One thing that greatly hampered communication was my cell phone running out of batteries. Although I had charged the batteries just before the trip, temperatures were cold enough that even with the phone stored inside my pack, temperatures left me with only a few minutes worth of battery life. However, I was able to milk juice from the battery throughout the next two days by storing the phone inside my jacket, warming it with body heat.

Cell phone batteries can behave drastically different in the cold (e.g. Tom's I-Phone never had battery problems, but it had reception issues), so for cold winter climbs either make sure you know at about what temperatures it keeps power when stored inside your pack, or keep it inside your clothes if you want the batteries fresh and ready for an emergency call.

Also, my altimeter stopped working on my descent on account of the cold and rime build-up, leaving me with only a map and compass to navigate. This is an example where I would have been in big trouble if I were

dependent on a GPS.

Unknown Unknowables and Wind on Mt. Shasta

When dealing with risk, it is helpful to break down some of the hazards into the categories of:

- Known knowables

- Known unknowables

- Unknown knowables

- Unknown unknowables

These are common labels used in risk assessment, and I’ve incorporated much of what I have learned in risk assessment and crisis management to climbing:

Known knowables are things such as what one learns from an avalanche safety course. For example, slopes that can potentially slide, and whether you are on or beneath one. These tend to be factors in accidents when people ignore warning signs as they are rushed to get down, focused on the summit, overconfident, etc.

Known unknowables are things that one can never know, but they can at least be aware of them. For example, where the trigger points are for an avalanche. These play into one’s uncertainty in assessing risk.

Unknown knowables are bad, as these are basically things you could have known, had you taken the time to investigate and learn. These lead to

preventable accidents. Reactive approaches to preventing future accidents also deal with these.

Unknown unknowables are things that one can never know that the one is unaware of. These are often things that become known only through a creatively morbid imagination, a near-miss, or an accident, and these are a common source of accidents.

In retrospect, I’ve learned some things about the wind on Mt. Shasta, turning some unknowns into knowns for me, which I’ll elaborate on here.

Weather Forecasts

Apparently, the NOAA forecast, when predicting winds, uses models for predicting typical surface winds from incoming weather. Mt. Shasta, due to its prominence, and due to the lack of drag in early season when snow coats the mountain, creates much stronger winds and venturi effects, leading to forecasts underestimating wind speeds. It has been suggested that NOAA forecasts for the mountain use wind-speed models for the winds several thousand feet above the ground. So forecasted wind speeds are a much greater unknowable than I had realized.

(The Thursday forecast that I had last checked forecasted calm to moderate winds on the mountain.)

I’ve long feared bad weather on Mt. Shasta – especially the wind – and I treat the mountain with respect. Knowing this detail about the forecasts will cause me to assume greater wind speeds than forecasted, and that such forecasted wind speeds are likely to be much less accurate than even the highly inaccurate general weather forecasts for the mountain.

Localized Winds

I figured that high winds on the mountain would be obvious, either in terms of snow plumes, lenticular or lee-wave clouds, or increasing winds as one climbed higher. It never occurred to me that the winds on the mountain could be so localized that you could be in calm weather at one location, only to turn a corner or gain or lose a few dozen feet only to be buffeted by +70 mph winds.

![Mt Shasta Tragedy - Day 2 Winds]() Distribution of winds encountered on day 2

Distribution of winds encountered on day 2

Now I know that despite weather forecasts indicating lower wind speeds, and all signs showing nothing but, that you can still have nasty surprises like this hidden from view – a particularly nasty known unknowable. Also, beware loose snow, as then it can be difficult to tell the snow plumes from lower-speed winds from the higher-speed winds.

![Mt Shasta Tragedy - Day 3 Winds]() Distribution of winds encountered on day 3

Distribution of winds encountered on day 3

The only takeaway lesson that I see from this is the increased importance on being prepared for adverse weather on the mountain (such as those things listed in the next section), and realizing the greater uncertainty in reading wind signs on the mountain.

What Made the Difference

One thing worth pointing out from the Mt. Shasta tragedy is that it came out as well as it did. Tom was in a good shelter and quickly found. I made it down alive, and with little more than some mild frostbite and cold injuries to my fingers and toes. I could have easily developed serious frostbite all over my face and hands, or this easily could have been one of those mountaineering accidents where we both disappeared on the mountain. I didn’t think much of my actions at the time, but others have pointed out how unusual or unique some of the important actions were, and that I should point them out for the benefit of other climbers.

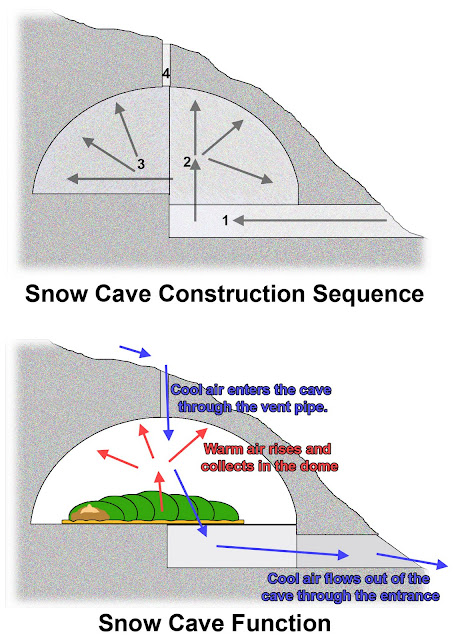

Snow Shovels & Snow Shelters

How many climbers are proficient at constructing a variety of snow shelters? Especially snow caves? How many of those carry a shovel in situations like a day climb to the summit of Mt. Shasta?

After talking with a number of climbing friends, the impression I’ve gotten is that not a lot of people can answer ‘yes’ to

all of these questions. Yet, my being proficient at building snowcaves and having the means to do so was critical in the outcome on the mountain.

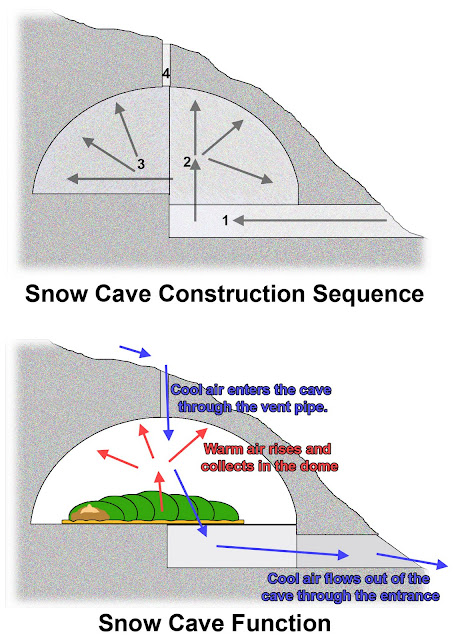

|

| The ideal snow cave & its construction sequence. |

Snowcaves are much more difficult to construct in practice than in theory. Finding sufficiently deep snow is difficult, and digging one quickly, without burning out, and without getting drenched, is very difficult. I try to dig at least one snowcave every season, if not more. If I don’t find an opportunity on a climbing trip, I make an outing to the mountains specifically to practice this skill (among others). I attribute this

regular practice with my ability to construct two snowcaves in one

long day under very difficult conditions.

If I hadn’t tried making snowcaves in such differing conditions, I might not have had the quick-thinking to figure out where to look for a site under the high winds that were scouring most of the snow away. There were very few places from the summit to the base where one could have been constructed, especially in low visibility and with the wind limiting mobility.

|

| Portable snow shovel. A broad, metal blade is best for shoveling large amounts of snow and cutting through hard layers. |

I often bring a snow shovel to summits that are in exposed areas prone to bad weather precisely for the purpose of being able to construct a snow shelter, and without the shovel, I wouldn’t have been able to dig either snowcave. Climbers should consider this use beyond just the extreme conditions that I ended up in. For example, what if you’re climbing Mt. Shasta or some other peak that requires a large effort to descend, and someone in your party experiences an injury, such as a broken bone or a tweaked muscle? What if you got lost in the dark coming down? You might have to spend the night, and being able to make a snow shelter would make this much safer.

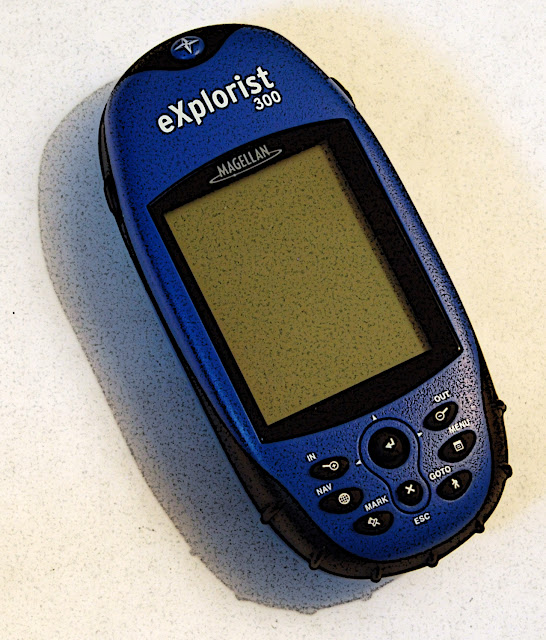

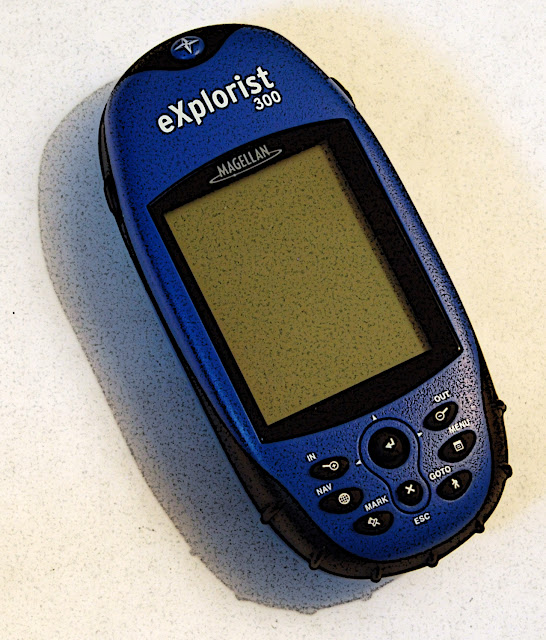

Orienteering Skills (without a GPS)

|

| Your best navigation friends. |

Many people like to use GPS devices. While I see the benefit when you need to be very exact in location, such as in locating caches, I emphasize the importance of using a map, compass, and altimeter first. These old-fashioned techniques, though less accurate and less convenient (or more so, depending on your satellite coverage), are much more versatile and robust.

Any climber should be proficient in orienteering and should always have a map, compass, and altimeter with them

in addition to a GPS device.

|

| A GPS can be good to have, but it shouldn’t be your primary navigation tool. |

On my descent, my digital altimeter froze up and died, and if I had a GPS device, it probably would have done the same. What allowed me to stay on route and get myself off the mountain and to rescuers was having a map and compass along, and being proficient at reading them and matching the landscape to the map.

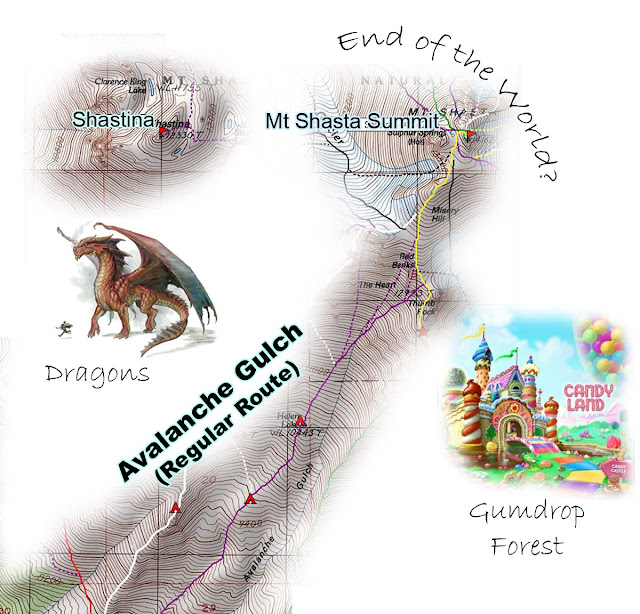

Knowledge of the Mountain (Beyond the Intended Route)

| |

| Not knowing the mountain outside your route leaves you with fewer reasonable choices for a backup route. | Routes considered for alternate descents when winds made our planned descent route too dangerous |

I knew many of the alternative descent lines besides the Bolam-Whitney Ridge. This gave me options of where to descend with an ability to take the safest and easiest one available. Knowing the mountain well allowed me to pick my way down the mountain and avoid hazards. I would have been much more likely to get lost in such bad visibility if I wasn’t so familiar with the mountain.

Even though this was my first visit to the north side of the mountain, I had familiarized myself well enough with the routes and terrain that I had a good mental map of the area. Tom had done the same, so we were able to discuss travel decisions on an equal level.

Extra Clothing

Even though the sun was shining, the skies clear, and the weather seemingly better than our first day on the mountain, I brought along my down jacket with a hood, my facemask, my warmest mittens, and liners that I could wear inside of the mittens. Not only did this make bivvying far more pleasant, but it saved me from hypothermia and frostbite.

Considering that the frostbite on my fingers was limited to the tiny area where my liner had come open, I’m sure that both my hands would have had terrible frostbite if I didn’t have liners to wear when operating my zippers and holding the map, or if I didn’t have such warm mittens. The same goes for wearing a facemask.

The blowing wet snow made it impossible to see with my eye protection as it fogged up and streaked with water, but the hood of my jacket provided enough cover that I could still see well enough to navigate in the white-out with my eyes exposed.

Extra Fitness

I was not pushing myself to my limit to make the summit. Although I worked myself pretty hard, I’ve had enough experience subjecting myself to endurance events that I knew how hard I could push myself while still leaving reserves of energy. For example, although it isn’t terribly fun, about once a week I push myself to climb the Stairmaster for an hour, with 10 lb ankle weights and a 60 lb pack, with an aim for punishment and covering as much elevation as I can – then I go and climb for 2 more hours, sometimes while wearing boots and a 30 lb pack.

I always aim to push myself for power or endurance on my bike rides, runs, and swims, and I try to get out in the mountains as much as possible. When I'm on easier climbing trips I often carry more weight, including other people's gear, as 'training weight' in order to improve my climbing fitness.

It was extremely physically wearing caring for Tom, digging two snowcaves, and down climbing the full north side of Mt. Shasta in 80-100 mph winds after a long day of climbing, a night out, and insufficient food and water to be hydrated and well-nourished. Having so much extra fitness, a trained ability to recover quickly, and a good sense of how to pace myself were critical in being able to make it through the weekend.

Decision Making

There were a number of ways I dealt with the stress of the situation that made a critical difference in getting down safely and marking Tom’s location.

In a nutshell, I’d say that my ability to make good decisions under pressure was my ability to maintain good

situational awareness . I was constantly assessing the situation – my physical and emotional state (as well as Tom’s), the landscape around me, the environment around me, the equipment I had, and the experience I had. I was thinking of relationships between these factors and what decisions to make in light of the full picture.

For example, in being self-aware, as I became more panicked, I managed to acknowledge these feelings, but to not be overwhelmed by them. I would slow down, calm down, and force myself to think through the problems rather than reacting to them.

Another was my physical state, as I had to decide when to stop. If I had continued down the mountain too far, I easily could have become too exhausted and cold to dig a snowcave. I made sure to get down the mountain far enough to be reasonably likely to make it out the following day, but once I realized that I was wearing out, I knew that it was time to recover before I was spent.

Attitude toward Climbing

I seem to stand apart from my friends in how much I read up on concepts ahead of time, how hard I work to remember the concepts I’ve studied, and how much emphasis I give to practice – not only in climbing techniques, but also in first-aid, wilderness survival, and self-rescue. This point is underlying many of the topics already discussed, but I felt it should be called out since this attitude affects everything else, and it paid off for me big time.

|

| Pinar learning the value of having a climbing pack pre-rigged to jettison onto the climbing rope in the event of a crevasse fall. |

For example, having a morbid imagination is a good thing. Imagining and discussing the ways you can die, get injured, or become separated while climbing allows one to be better prepared – provided that such imaginings are given realistic weight. Such visualization helps inform me into what to bring, what to practice, and whether I really should be doing what I am doing at the time (e.g. climbing without a rope). As far as what to bring, in the past I’ve often heard people suggest leaving a particular safety item behind because we probably won’t need it. While this can be all right within reason as you can’t bring everything with you, you should be wary of the pitfall of just assuming that you won’t need the gear.

I’m always trying to be safer and better prepared, and although it is an unobtainable goal, it is one worth striving for. To put the attitude succinctly: No one ever plans to have an accident, but they should plan to be prepared for one.

A Word on Why You Shouldn't Believe Early Media Reports on Mountaineering Accidents

Some people still seem to insist on believing what the media reported over what I had to say about what happened. Well, my claiming that their earlier reports are false and not to be believed is not a defensive or paranoid reaction.

I learned a lot from Mt. Shasta as to how little research is done before reporting something as fact. And once one outlet makes a claim, even if it is unfounded, many of the other news outlets then reference that claim as fact rather than checking up on it. I witnessed this first-hand as stories were first reported locally, then repeated nationally, and then repeated internationally.

Here are a few examples of the sloppiness of the earlier reports, which should cast doubt on their ability to report the finer details of a topic that they were unfamiliar with:

1. Tom was said to be engaged to be married. He was not.

2. I was said in the days after Shasta to have returned to Berkeley and was reunited with my father. This was news to me, since I stayed at the town of Mt. Shasta to meet the family and wait around for Tom's recovery. Such a reunion happened a week after the media reported it.

3. In many reports, the articles couldn't even keep the names 'Tom Bennett' and 'Mark Thomas' straight, and some articles even had 'Tom' performing CPR on 'Mark'.

4. The mountain was reported as being closed to climbing. Mt. Shasta is never closed to climbing.

5. We were reported as climbing the mountain without permits. We had all the permits that were possible for our approach.

6. When the media couldn't find credible people to interview for the early stories, they went so far as to interview gym climbers and ask them to speculate on the accident.

As far as I know for how I was approached by the media, and what those involved in the rescue reported, there was virtually no fact-checking done on anything reported. The attitude of the media was that if they couldn't verify a fact, they would make a best guess and report that. So consider that this is how many agencies operate whenever you see a television or newspaper story.

Comments

Post a Comment