-

4584 Hits

4584 Hits

-

0% Score

0% Score

-

0 Votes

0 Votes

|

|

Trip Report |

|---|---|

|

|

48.77734°N / 121.8132°W |

|

|

Nov 24, 2013 |

|

|

Mountaineering, Skiing |

|

|

Winter |

- The Mountain

Mt. Baker has the second largest glacier in the Cascades, and outside of Alaska, one of the top ten in the contiguous U.S. Maintained by a huge load of annual snowpack, the group of glaciers on Mt. Baker, the Coleman, its north facing glacier is the largest. The Coleman glacier is an enormous icefall a couple kilometers long, marking the boundary of the skiable section of the mountain. The Coleman-Demings mountaineers route passes through a higher section of the glacier where snow crevasses are just starting to form that are traversable, but as the glacier pours over the steepest section of the mountain, the weight of it deforms quickly into dense ice, making a solid falls of vertical slabs.

The weather window had just opened for Mt. Baker. A cold front promising clear skies, and low to no wind was here, November for a full week. This meant a chance to be on the mountain at its most stunning.

A few different scientists using a few different methods have determined that the glacier is moving 1.5 feet per year, and contributes to river runoff in the summer time. This glacier is predicted to be here for another hundred years which means that you and future generations will still get to be on it, well after the glaciers in GNP, Sierra Range have gone. Its size and loadability are some of the biggest in the contuminous US. During the Last Glacial Period, the Coleman was part of a larger ice cap that covered the mountain.

2. The Glacier

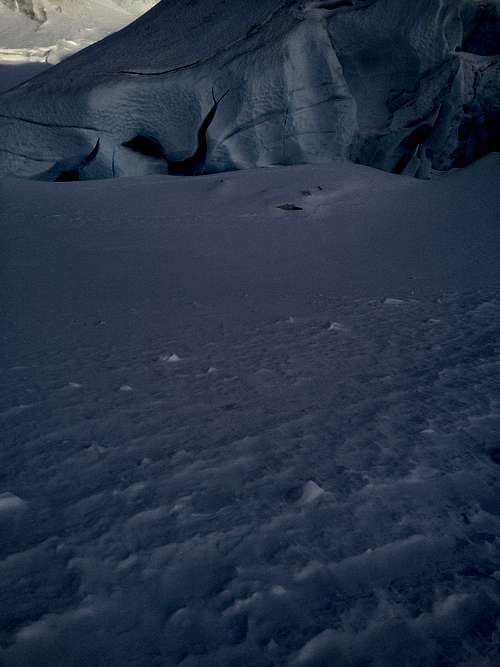

The historic terminal moraine is hundreds of meters deep, where the historic glacier stood during the Last Glacial Period, and the USGS found this glacier to be growing, even into the 50’s. Even with all this going for it, it isn’t expected to be around for many more generations. Estimates of mass balance generally agree that today the Coleman glacier is retreating. Most of the glacier is icefalls, making for difficult navigation over blocks or slabs of ice 10-20 feet high. (The mountaineers route bypasses this technical section.) Annual snowfall packs down further on older layers of snow and ice, causing deformation of snow crystals and increasing density with depth as crystals strain and compress further, making ice. With gravity acting downward, the density increases downwards, and as the glacier moves across rocks deep below that compaction eventually opens upwards into crevasse. There may be ice caves in the Coleman, as there are in the Sandy Glacier. They wait to be discovered. The middle section of the glacier is the most dense, with blue ice, and there are slabs all the way to the terminus.

3. The Route

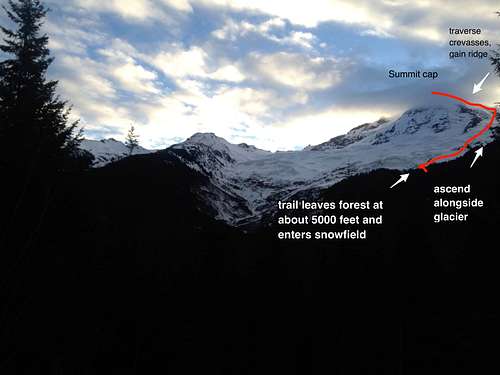

The mountaineers route is a slog for a couple miles on a forest trail, and then once above treeline, ascends next to the Coleman, traverses it at the top of the glacier, where snow field is deep. The snowfield is hundreds of feet deep at this point, and one can easily navigate the few crevasses that reach the surface. This is the only point on the route that the climber is on the glacier. Once above the top bergschrund, the route follows the ridge directly to the summit crater. The slopes go from ashort 35 ° pitch to a sustained 20 °. Gaining the Ridge, the wind picked up tremendously, and a few sections of steep and icy terrain required our full attention. This pitch turned a few other climbers away that day.

This is a great area to explore. Total ascent is over 5000 feet. We summited fast enough to get down in alpenglow.

This mountain loads more snow than any other in the Pacific Northwest. Although there are noise fields in the US, this is some of the most continuous mountain glacier. Expect bad weather, plan for bad weather, and if you find a good weather window, go for it.

It was so nice when we were there that we saw three ptarmigan, nonchalantly fed on seeds from the rare bushes still coming up through the snowpack. One took off running across the snowy slope for shelter, and the other two just watched. As I approached, the second one hesitated, then ran off to find Running Bird. The Last Bird stood his ground, and didn’t mind me, so I got a good photo of him.