Introduction

![August 2003 - The Palisades...]() The Palisade Glacier in the fall (Palisades, Sierra Nevada, CA)

The Palisade Glacier in the fall (Palisades, Sierra Nevada, CA)What is a Glacier?

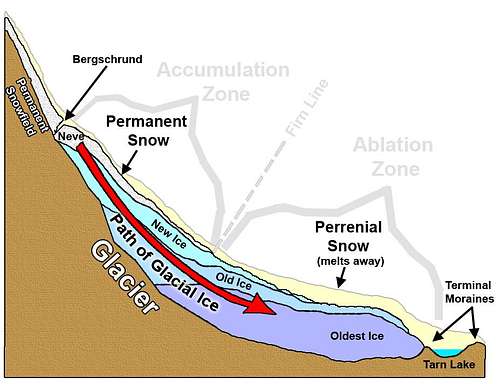

Say you’re climbing in the mountains in late fall and you come across a body of snow that has been there for the whole summer, if not for years. Is it a glacier? Maybe, maybe not. Even if it has metamorphosed into ice, it still may be a permanent snowfield. The critical feature that glaciers have is movement.

The glacier may start out as a permanent snowfield or icefield, but eventually, the weight of the ice becomes so great compared to the friction holding it in place that the body of ice moves downhill. At the same time, enough new snow is added to the glacier to constantly replenish the ice at the top of the glacier.

The area of a glacier that retains snow year-round is called the accumulation zone, and as the ice compacts, it moves downhill to an elevation where more melting occurs on the surface and eventually the presence of ice is due solely to ice that has moved downhill rather than remaining from prior years.

This area of the glacier that completely melts out is called the ablation zone. The dividing line between the accumulation zone and the ablation zone is the firn line, and in mid-latitude glaciers it is easily visible, as in the photo above, as the lingering snow stays whiter while the melted out ablation zone is left dark and dirty in late season.

Can you spot these features on the Palisade Glacier, pictured above? If the glacier is in equilibrium, the head and terminus of the glacier will remain stationary as the melt at the bottom matches the addition of ice at the top. Although the glacier may appear stationary, it is still moving and eroding. Glaciers recede or grow when the formation of ice at higher altitudes becomes out of balance with the melt of the glacier at lower altitudes. The movement of the firn line is an easy way to tell if a glacier is growing or shrinking.

![Diagram of a Glacier]() A diagram of what a glacier is and how it works. Ain’t it cool? ;-)

A diagram of what a glacier is and how it works. Ain’t it cool? ;-)Some Types of Glaciers

![Mt Fay]() Two hanging glaciers on Mt Fay. Notice how the upper one has nearly split in two! (Canadian Rockies, Alberta, Canada)

Two hanging glaciers on Mt Fay. Notice how the upper one has nearly split in two! (Canadian Rockies, Alberta, Canada)Rock Glaciers

Sometimes the firn line moves beyond the top of the glacier, so the entire glacier melts away. However, if enough rocks fall onto the ice, the rock will act as an insulator of the ice against the heat, preserving the ice beneath. The glacier may look like just a flowing pile of rocks, but there may still be ice flowing underneath.

Hanging Glaciers

Hanging glaciers are glaciers that do not melt out at the bottom. Instead, the glacier plunges off of a cliff. The terminus is an icefall of seracs. These glaciers appear to be hanging on the mountainside, and it is generally a good idea not to linger below them, as they are always dropping massive chunks of ice off the cliff, creating devastating ice avalanches.

Miscellaneous Glacier Features

Moulins

Moulins are holes in the glacier burrowed by flowing water. During the summer months when there is a lot of melting, water may pour down the surface of a glacier like a river. If this water hits a small crevasse, the water will erode the ice and burrow down, sometimes to the bedrock, creating a subterranean river. Moulins are very hazardous as if you fall into meltwater on a glacier, you may be swept into one of these and into the depths of the glacier and you will probably drown. They are found in ablation zones and usually form or open up in the later season when a lot of melting is occurring.

![Glacial River & Moulin]() A river forms on the surface of the Athabasca Glacier during intensive summer melting (left), disappearing into a moulin formed in the longitudinal crevasse near the glacier terminus (right). (Icefield Parkway, Canadian Rockies, Alberta, Canada)

A river forms on the surface of the Athabasca Glacier during intensive summer melting (left), disappearing into a moulin formed in the longitudinal crevasse near the glacier terminus (right). (Icefield Parkway, Canadian Rockies, Alberta, Canada)![Upper Dinwoody Glacier]() The Dinwoody Glacier. You can clearly see the bergshrunds lining the tops of the glaciers. The white snow is the accumulation zone, and the darker ablation zone can be seen in the lower left corner. Also note the melt channels, which are a sign of snow stability, but also potentially weaker snow bridges (Wind River Range, WY)

The Dinwoody Glacier. You can clearly see the bergshrunds lining the tops of the glaciers. The white snow is the accumulation zone, and the darker ablation zone can be seen in the lower left corner. Also note the melt channels, which are a sign of snow stability, but also potentially weaker snow bridges (Wind River Range, WY) Bergschrunds

Bergschrunds are the gaps formed by the separation of the moving glacier and any stationary ground above, which is usually a permanent snowfield or ice couloirs. They can be very wide and broad, but generally aren’t as deep as crevasses as they tend to fill with debris falling down from above the glacier. Bergschrunds provide major barriers to exiting a glacier or entering a couloir as once snow bridges melt out, they can form continuous vertical or overhanging walls of ice.

![Bob & the Bergschrund]() Bergshcrunds often make it difficult to exit a glacier (Middle Palisade Glacier, Sierra Nevada, CA)

Bergshcrunds often make it difficult to exit a glacier (Middle Palisade Glacier, Sierra Nevada, CA)Moats

Because the darker rocks along the edge of glaciers absorb heat from sunlight, they tend to melt away the snow and ice adjacent to it. Although moats can be tens of feet deep and wide, they are generally smaller than crevasses. Still, they can pose barriers to entering or exiting a glacier, similar to bergschrunds.

Glacial Erosion

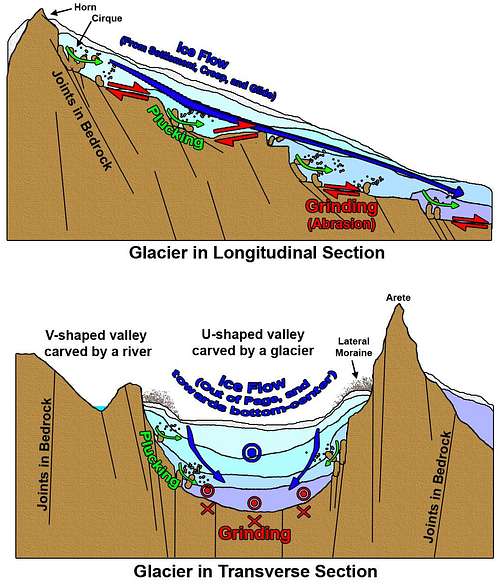

Plucking & Grinding

A glacier erodes through two processes – plucking and grinding. Grinding occurs as the ice abrades rock and wears it down. Rock worn by a glacier is easily identified by the smooth glacial polish left behind from this. Contrary to popular conception, this is not the main mechanism of glacial erosion, as rocks such as granite abrade too slowly to account for the deep U-shaped valleys carved by glaciers. Plucking is the main erosion mechanism of glaciers.

All rocks have some cracks in them (also called joints). These are formed by the presence of tension. In granite and other metamorphic rocks, joints often form from the contraction of the rock as it cooled. These joints are weaknesses in the rock, and glacial ice tends to catch the edges of joints and ‘pluck’ out shards of rock, peeling back the rock layer by layer. Because of this, heavily jointed rock wears down much more quickly and dramatically than rock free of joints. T

his is also why although the bottoms of glacially carved valleys are smooth and rounded, the sides and headwalls of such valleys are usually very steep and often left as a continuous line of cliffs. This is also why glacially carved canyons often have fairly flat bottoms interrupted by a series of distinct headwalls, called cirques. Parallel glacially carved valleys tend to leave knife-edge ridges with very steep rock faces on both sides. These ridges are called arêtes. Alternatively, valleys eroded by water are V-shaped and twist and turn as water is deflected by various types of rock. The large mass and inertia of glaciers create straight valleys as glaciers usually ride up and over, or spill around any obstacles that aren’t flattened by the glacier.

![Diagram of Glacial Erosion]() Glacial erosion through grinding and plucking.

Glacial erosion through grinding and plucking.Remnants of Glacial Erosion

Glacial Till

Glacial till is the soil eroded from glaciers. Usually, this till colors water, leaving runoff close to the glacier a milky white color. Depending on the type of rock eroded, this can have dramatic coloring effects further downstream, creating lakes and rivers that are unreal shades of blue, green, and turquoise. Glacial till also makes water gathered from the toe of the glacier undesirable for drinking as it is essentially muddy water. It also is hard on water filters.

![Mt Biddle & Lake McArthur]() Lake MacArthur and Mt Biddle. (Yoho National Park, Canadian Rockies, BC, Canada)

Lake MacArthur and Mt Biddle. (Yoho National Park, Canadian Rockies, BC, Canada)![Lake McArthur & Mt Biddle]() Lake MacArthur and Mt Biddle. (Yoho National Park, Canadian Rockies, BC, Canada)

Lake MacArthur and Mt Biddle. (Yoho National Park, Canadian Rockies, BC, Canada)![Cheakammus Lake]() Glacial till is what gives Cheakamus Lake its deep blue colors (Coastal Range, BC, Canada)

Glacial till is what gives Cheakamus Lake its deep blue colors (Coastal Range, BC, Canada) Moraines

Moraines are mounds of rock and dirt that are the debris pushed up by a glacier. In general, there are three types of moraines – terminal, lateral, and medial. Terminal moraines mark the toe or terminus of the glacier, forming across the width of the glacier. Lateral moraines form alongside the glacier as debris is pushed out from the side of the glacier or from debris that falls onto the edge of the glacier as the glacier undercuts neighboring cliffs. As the debris piles up, it protects the snow beneath from melting, causing these sides of the glacier to remain higher than the center.

Medial moraines form when two glaciers flow together, trapping lateral moraines between them. Once a glacier melts away, moraines are often the only clue of glaciation. Often the terminal and lateral moraines trap water in the valley carved by the glacier, forming a lake where the toe of the glacier once stood. This is how many of the natural lakes and ancient moraines at the mouths of the canyons in the eastern Sierra formed. Glaciers are always growing and receding, so there are often multiple terminal moraines as the glacier pushes one up, recedes, and then pushes up another.

Meltwater from the glacier tends to pile up behind these moraines, forming lakes at the toe of the glacier, called tarns. If a glacier recedes slowly enough, it may do this in many locations along its track, leaving behind a string of lakes, such as the “Numbered” lakes in the North Fork of Big Pine in the Palisades region of the High Sierra. Because moraines are formed by eroded rock and mud pushed up into mounds, they are composed of rotten, friable rock and are very unstable. Not only are they formed in an unstable way, but moraines by existing glaciers are still being pushed.

Climbing on moraines is unpleasant and can be dangerous due to falling rock. Take care whenever climbing on moraines and strategize ahead of time to take the line of lowest steepness as the moraine is more stable in these areas. On some large moraines, enough mud and soil can collect on top to support plant life, such as on the toe of the Ruth Glacier. These moraines essentially become moving meadows and forests!

![More Glacial Beauty]() A prominent medial moraine on the Ruth Glacier. You can see lateral moraines on the side. Also note how many of the crevasses are filled with melt water as this was taken in June. (Ruth Gorge, Alaska Range, AK)

A prominent medial moraine on the Ruth Glacier. You can see lateral moraines on the side. Also note how many of the crevasses are filled with melt water as this was taken in June. (Ruth Gorge, Alaska Range, AK)Cleavers, Nunataks, and Roche Moutonnees

A cleaver is a ridgeline of rock that remains sticking up between various flows of a glacier, like a fin. They can provide means of climbing through a glacier that has heavy crevassing or an icefall. The easiest and most popular route on Mt Rainier, Disappointment Cleaver, ascends a cleaver to pass between the icefalls of two neighboring glaciers to reach the summit. A nunatak is an exposed rocky element of a ridge, mountain, or peak that protrudes above the ice of a glacier or icefield. A number of the peaks in the Sierra Nevada are ancient nunataks. Roche moutonnee is a rock or hill sculpted by glacial ice flowing over the top. Usually the uphill side is scoured smooth by the grinding action of the ice, but the downhill side has a steep, fractured face that is left from glacial plucking. Many of the domes in Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite National Park are actually remnants of ancient roche moutonees.

![Lembert Dome Overview]() Lembert Dome is a Roche Moutonnee. The glacier flowed from right to left (Tuolumne Meadows, Sierra Nevada, CA)

Lembert Dome is a Roche Moutonnee. The glacier flowed from right to left (Tuolumne Meadows, Sierra Nevada, CA)Glacial Kinematics

In this section I will talk briefly about the behavior of glacial ice and how it affects the form of a glacier.

Creep and Glide

Glaciers move by a combination of glide and creep. Because ice is plastic when deformed slowly and under pressure, the glacial ice flows downhill like a slow river of ice. Creep is this movement by deformation. Glide is a rigid-body motion of the glacier as it slides down on a bed surface, usually lubricated by meltwater that flows between the bedrock and the underside of the glacier. Creep is what causes plucking, and glide is what causes grinding in glacial erosion. In general glaciers move faster in the summer, both because the greater melting accelerates glide, and also the warming of the ice makes it flow easier, accelerating creep. As such, icefall activity tends to increase during the summer months if it has any variation over the year. Because heat accelerates glacier motion, mid-latitude glaciers can move very fast, reach 1-3 ft of movement per day!

Kinematic Waves

Because glacial ice flows, it has many characteristics of a liquid. One is the formation of kinematic waves. These waves are essentially slow-motion shockwaves in the ice that form from very heavy snow years and take years to propagate down the length of the glacier. The increase in load from the extra snow pushes the glacier down harder. When this snow melts or consolidates into the glacier, the glacier springs back up again.

This up and down motion travels down the glacier at a slow pace, but the size of the wave can be quite noticeable. The waves can reach 80 ft in height and move down the glacier faster than the flow of the ice itself, causing the terminus of the glacier to advance dramatically when it reaches the end. Keep in mind that these waves tend to accelerate the ice, which affects seracs and crevasses. At the front of the wave, crevasses tend to shrink, but may then become much larger behind the wave as the ice goes into tension. The waves would also increase the rate of serac fall as the wave passes through icefalls.

Glacier Surges

Sometimes the speed of a glacier increases very suddenly, causing a surge in the ice, sometimes of up to 30 feet in a day. This may be from a combination of accelerated glide, creep, and kinematic waves. Critical mass of the glacier or sudden detachment from the base rock layer may be other contributing factors. These surges can completely change the nature of a glacier, making a once passable glacier completely impassable due to the spread of icefalls and crevasses. The Muldrow Glacier on Denali used to be an easy walk up until it surged in 1956. Now climbers must climb around the glacier or fly over it.

Crevasses

Ice Under Tension, Compression, and Shear

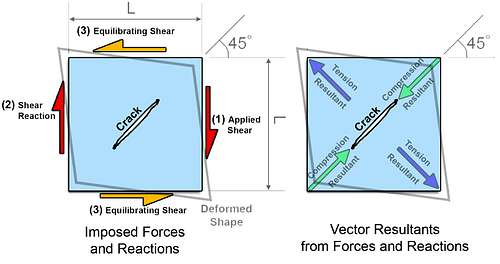

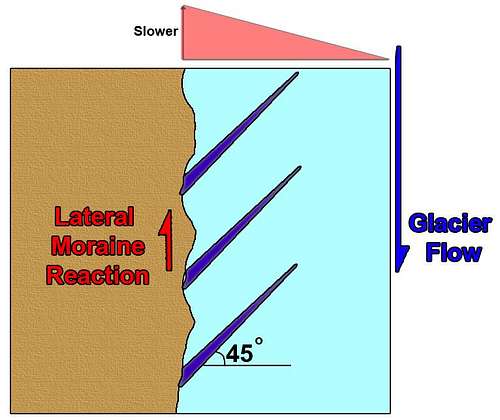

Ice is weak and brittle in tension, and strong and plastic in compression. This basic tendency explains much about the formation of crevasses on glaciers, and the understanding of this behavior and where it occurs is key to understanding crevasses and knowing where to expect them. This knowledge is important in planning a route across a glacier, especially if crevasses are buried but you want to minimize the likelihood that you are crossing snow bridges. In general, crevasses form in tension zones, where the ice undergoes tension.

Compression zones on glaciers have few if any crevasses and are generally the way to go for route planning and choosing camps. These zones are formed by direct tension-compression of the ice as the glacier bends, or as a result of shear in the ice that occurs from flow differential. The figure below shows the relationship between shear and tension. This is important as it explains why crevasses have the orientation that they do, which is also important for predicting crevasse patterns on a glacier. Basically, if a block of ice is subjected to shear (1), say from faster flowing ice, it develops an equal and opposite reaction (2), say from slower-moving ice or the stationary ground. These forces would cause the ice segment to spin, except it then develops equilibrating shears (3) perpendicular to (1) and (2). These shear forces can be added up vectorially to get the resulting tension and compression forces, which are equal to [2*shear force]0.5 and occur at 45 degrees to the direction of shear.

![Diagram of Cracking Ice]() Force diagram of a square segment of ice.

Force diagram of a square segment of ice.Types of Crevasses

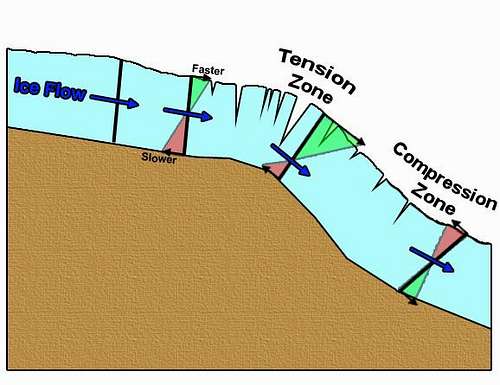

Transverse Crevasses

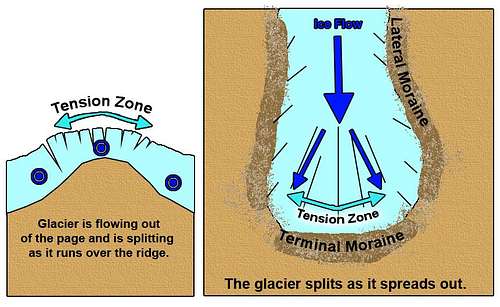

When a glacier travels over a convex surface, such as flat ground rolling into a steeper slope or the glacier rolling over a low bulge, the ice layer bends as the top layers are put into tension and the bottom layers are compressed. Another way to think of it is that the top layer must accelerate to keep up with the bottom layer as it sweeps over a greater distance to round the bulge. This tends to pull the ice apart. Because the tension develops along the fall line, transverse crevasses tend to form as straight crevasses across glaciers, perpendicular to the flow. Conversely, at the bottom of drops or in bowls, the ice is in a compression zone and is generally free of crevasses.

![Transverse crevasse formation..]() Transverse crevasse formation.

Transverse crevasse formation.Marginal Crevasses

Marginal crevasses form along the sides of a glacier due to the differential flow of the ice. Glaciers move faster in the center than at the edges, which are restrained by the stationary rock on the sides and beneath the shallower ice. This difference in flow rate causes shear in-line with the glacier flow, which causes tension to develop along 45o angles facing into the flow.

So in general, marginal crevasses form at the edges of a glacier at 45o angles facing into the flow. They can create barriers to entering and leaving a glacier, but routes can be planned through them so long as they cut diagonally onto the glacier in line with the crevasses. It is because of the continual development of marginal crevasses that routes usually travel down the center of the glacier, because crevasses there are more intermittent. Also, keep in mind that the ice between the crevasses is under compression (remember the ice shear figure?), but may be in slender strips. This could leave those sections of the glacier prone to buckling and crushing, making even these sections impassable.

![Marginal crevasse formation.]() Marginal crevasse formation.

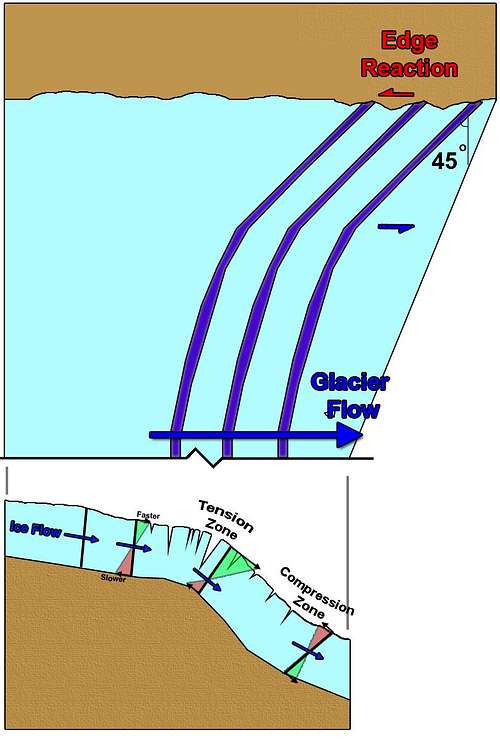

Marginal crevasse formation.Transverse Crescentric Crevasses

Transverse crescentric crevasses are a blend of transverse and marginal crevasses and tend to form as a glacier rolls onto a steepening slope as it passes through a constriction. This bends the glacier over the rise while shearing the sides. The combination of these effects creates arc-shaped crevasses that usually span most of the length of the constriction. The arc is convex facing uphill and concave facing downhill.

![Transverse crescentric crevasse formation.]() Transverse crescentric crevasse formation.

Transverse crescentric crevasse formation.Radial Crevasses

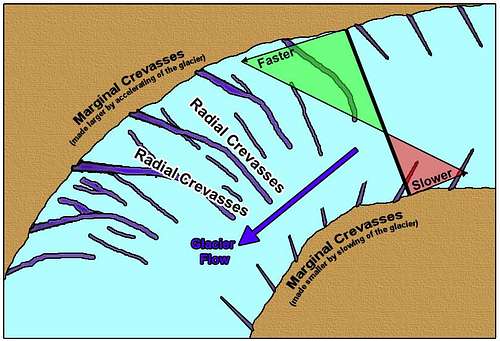

Radial crevasses form on the outside curve of a glacier as it rounds a corner. This outside edge travels faster to keep up with the flow, subjecting these outer regions to tension, creating straight radial crevasses, perpendicular to the flow, but radiating out from towards the center of the bend, like spokes on a wheel. Glacier routes tend to hug the inside of a bend because this region is generally free of radial crevasses and may actually be subjected to compression as the flow is slowed down here.

![Radial crevasse formation.]() Radial crevasse formation.

Radial crevasse formation.Longitudinal Crevasses

Longitudinal crevasses form parallel to the flow of the glacier. They may form as a glacier passes over a bulge or ridge in line with the glacier, but they usually form near the terminus of the glacier as the ice spreads out laterally and becomes shallower, making it more sensitive to the underlying terrain. Because they form in line with the fall line, they are usually less of a barrier to travel, but it is more difficult to travel safely around them as a roped team.

![Longitudinal crevasse formation.]() Longitudinal crevasse formation.

Longitudinal crevasse formation.Seracs & Icefalls

When a glacier flows off of a cliff or a very steep rise, transverse crevasses become so severe that the ice actually separates from the glacier, forming free-standing blocks of ice that may be as large as office buildings. These provide barriers to travel when they form in large numbers, often requiring technical ice climbing to pass through them. These areas are called icefalls and are the ice analogy of a waterfall.

Seracs pose objective hazards to climbers as they tend to topple, crushing anything in their path, or starting ice avalanches. Serac fall is often unpredictable, although it is more prevalent with faster moving glaciers. In summer as glaciers accelerate, the rate of serac fall may also accelerate, but this isn’t always the case. Traveling around them at night might not be any safer than traveling around them in the day. However, the rate of collapse tends to be characteristic of a glacier, so the amount of hazard or the timing of serac collapse can be deduced by watching the glacier for a day or so and keeping track of the activity.

![Approaching the Ice Arch in the 2nd Icefall on the Whitney Glacier]() Seracs on the Whitney Glacier (Mt Shasta, Cascades, CA)

Seracs on the Whitney Glacier (Mt Shasta, Cascades, CA)Identifying Crevasses & Icefalls from Topographic Maps

For safety, ease and speed of climbing, it is important to select good routes over glaciers. In general, routes should avoid climbing below or through icefalls, should enter and exit the glacier at strategic places, and to take a path of least resistance through the crevasses. Because of this, it is a good idea to scope out the glacier from a distance on the approach. You can also predict ahead of time where the easy and difficult sections or safe and dangerous sections are.

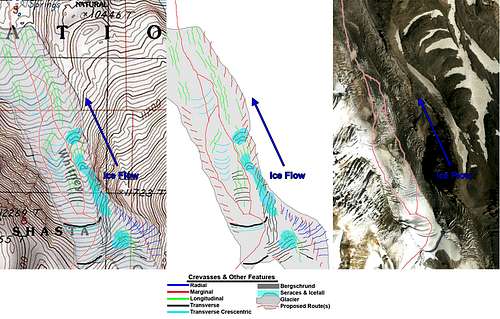

Based on the concepts I discussed in the previous section on crevasses, moats, and bergschrunds, you should be able to draw a rudimentary crevassing pattern on a topographic map. For example, see the figure below of the topo map, how I’d assume the crevasses are (and therefore where the easiest route goes), and a satellite photograph showing the actual state of the glacier.

![Determining Crevasses from a Topo Map]() Locations of seracs and typical crevasse types, with a standard line of travel shown. The crevasses were drawn & route selection theorized based purely off of the topographic map and confirmed once overlaid on a satellite photo.

Locations of seracs and typical crevasse types, with a standard line of travel shown. The crevasses were drawn & route selection theorized based purely off of the topographic map and confirmed once overlaid on a satellite photo.Identifying Buried Crevasses on the Glacier

When crevasses are buried under snow, it is important to spot them as soon as possible to make optimal route adjustments and avoid hazards. There are a number of ways to spot crevasses. In winter when there are no outward signs, the lead climber should regularly probe the snow with their ice axe or pole. Beyond this, there isn’t much one can do.

![Failing Snowbridges and Meltwater Channels]() It can be difficult to distinguish meltwater channels from crevasses.

It can be difficult to distinguish meltwater channels from crevasses.In later season as the glacier begins to melt out, snow bridges begin to sag. Buried crevasses can be spotted by looking for these sagging snow bridges. Linear undulations in the glacier are a sign, especially if there is cracking in the snow surface. As this layer melts out and drops down, the troughs tend to fill with dirt and dust, darkening them. This can happen in drops too subtle to see without discoloration.

However, keep in mind that these may not actually be signs of crevasses. In addition to just being chance features in the glacier, in later seasons melt channels form on the glacier surface, which can be confused with crevasses. Windblown snow can take the form of dunes across the glacier, creating ripples with dips similar to a sagging snow bridge.

So how do you tell crevasses apart from these false-positives? If you know where to expect them ahead of time, and what sort of orientation they should have there, then you can more easily discern the appropriate patters. For example, meltwater channels fall down the fall line, so unless you are worried about the formation of longitudinal crevasses, sagging snow in this orientation is probably not an indicator of a crevasse.

Whenever the rope team gathers together, for food breaks or for making camp, it is important to ensure that there are no buried crevasses in the area. The lead climber should probe the area around them (ideally with an avalanche probe, as ski poles and ice axes cannot probe very deep) and the campsite then belay the climbers in. Probing can be used to determine safe zone boundaries within the camp where climbers can walk around un-roped.

Glacier Travel & Rescue (Diagrams)

In brief, below are some graphics I made for illustrating some aspects of glacier travel and rescue.

Basic Glacier Travel Techniques

![Tie-In Lengths for Glacier Travel]() Tie-In Lengths for Glacier Travel Tie-In Lengths for Glacier Travel |

![Traveling Through Parallel Crevasses]() Traveling en-echelon while walking parallel to crevasses. Traveling en-echelon while walking parallel to crevasses. |

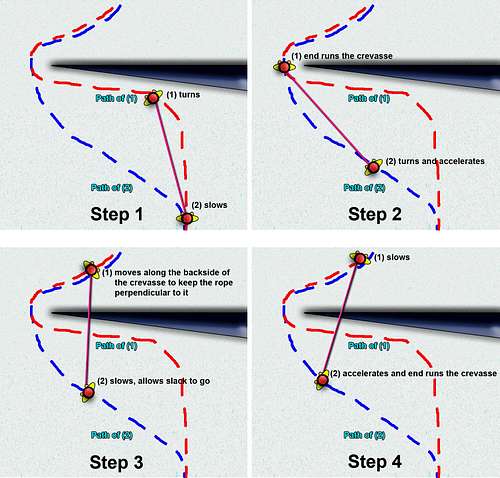

![End Running a Crevasse]() End Running a Crevasse

End Running a CrevasseSelf-Rescue for Crevasse Rescue

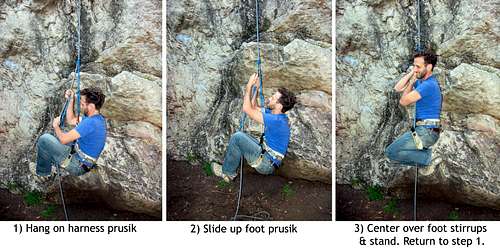

![Texas Kick]() Texas Kick - the standard way to ascend a rope. Just alternate sliding up the foot stirrup & harness prusiks

Texas Kick - the standard way to ascend a rope. Just alternate sliding up the foot stirrup & harness prusiks![Ditching a Pack]() Ditching a Pack. You can see how the pack is hanging on a pre-rigged tether. All that the climber needs to do is clip the tether to the rope and shed the pack. The pack then hangs as a counterweight as she ascends the rope using the Texas Kick system.

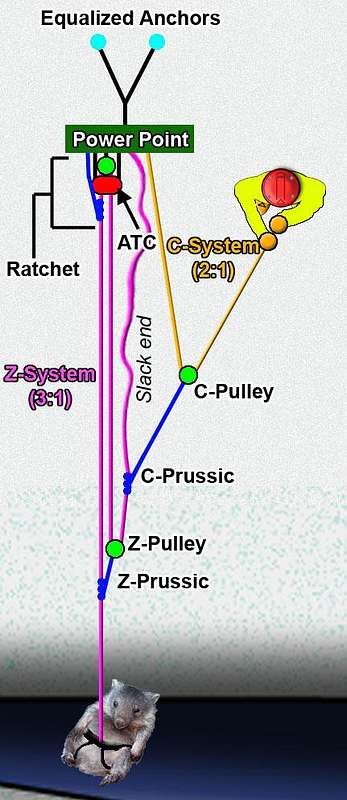

Ditching a Pack. You can see how the pack is hanging on a pre-rigged tether. All that the climber needs to do is clip the tether to the rope and shed the pack. The pack then hangs as a counterweight as she ascends the rope using the Texas Kick system.The Z-C Hauling System for Crevasse Rescue

![Diagram of a Z-C hauling system.]() Diagram of a Z-C hauling system.

Diagram of a Z-C hauling system.

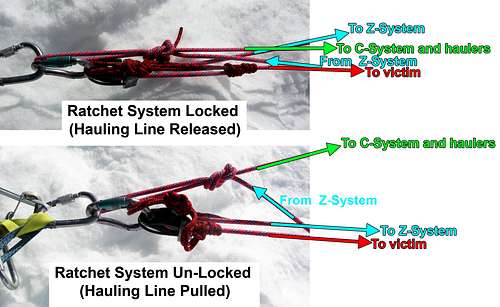

![Ratchet System for Hauling]() Ratchet System for Hauling Ratchet System for Hauling |

![A Z-C hauling system in action]() A Z-C hauling system in action A Z-C hauling system in action |

Bibliogaphy

The writings of this article were based off of information I learned from the following sources. Consult them for more information about glaciers and ice.

- Glaciers of California, by Bill Guyton.

- Mount Rainier: A Climbing Guide, by Mike Gauthier

- Glacier Travel & Crevasse Rescue, 2nd Ed, by Andy Selters

- Any basic mechanics of solids textbook

- Various internet wanderings

Links

Report on Personal Website

Comments

Post a Comment